Taken as a whole, the show just opened at Tew Galleries constitutes an unusually evocative meditation on nature, history, and the imagination through which we perceive both categories.

J. F. Baldwin’s dreamlike or visionary portraiture, paradoxically, is also derived from the most meticulous historical vision of John Singer Sargent. But what in Sargent is a vehicle for precision is in Baldwin the beginning of transformation: the exactness of the standing female figures is surrounded by or enveloped in misty texture, or is offset by surroundings that recall an exotica that belongs to more openly romantic nineteenth century fictions of things that were once but are no longer. Sargent’s concealed emotions or his latent romanticism become manifest in Baldwin’s transmutation of his pictorial strategies.

Deedra Ludwig does something similar with landscape, changing the relationship of plant, sky and weather by evoking atmosphere through density of color, rendering both literal and symbolic elements of, say, the Everglades (as in a recent residency) or more gentle territories of nature and the human spirit. Ludwig pours a great deal of her own emotional energies into these pieces, and the results range from infinitely appealing to seductively distressing…the sublime crawls around the edges of some of the work, and in the postmodern world, nature’s incommensurability with human purposes can sometimes feel scary.

Yet Ludwig is at home in it all, just as she is at home in her New Orleans studio; the post-Katrina scene in the Crescent City is not just revived but freshly energetic and distinctly visioned. Her move from the Pacific Northwest was good for her, though it seems to have imparted a fresh current to her work that some will find less congenial than the softer depths of previous paintings.

Whitney Stansell, though, is the real discovery of this show. Her paintings combine the style of 1950s children’s books with a real sense of invention that is promised by her series title “An Iconography for an Imagined History.”

On further investigation, every term in this title becomes problematic, so it’s worth stating first what these paintings appear to be when they are taken on their own terms, rather than with the knowlede of Stansell’s stated intent.

The scenes are rendered in the simplified detail of vintage children’s books and appear to depict a time appropriate to the rendering style. Only after considerable time does it become apparent that the outlines of the pastel images are produced with black thread.

Each scene contains numbers that correspond to a line of text in cursive handwriting that runs across the bottom of the painting.

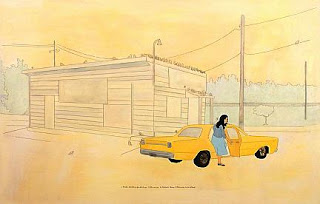

For example, The First Day of Work shows the young woman who features in most of the paintings in front of a building, and the legend across the bottom reads “1. Danelle O’Toole arrives for her first day of work. 2. Yellow taxi cab. 3. Antonucci’s Bakery. 4. Birds waiting for day old bread.”

Here and in all the other paintings, the strategy replicates a New Yorker cartoon. Number one is the set-up line. Number two is self-evident. Number three is an incongruously exact detail that further explicates number one, and therefore wouldn’t have been funny had it simply been number two, without the obvious taxi inserted in between. Number four is effectively the punch line, because it is an element that has nothing to do with Danelle O’Toole, though it might tell us something about the nature of the bakery. (Lots of bakeries wouldn’t feed their day old bread to the birds, especially not nowadays.)

Something about every one of the paintings suggests a joke in progress, in fact. Usually at least one punch line arrives in each, though sometimes the joke is multi-level.

This applies even to the diptych Before and After, where the first shows a child being led by the hand across a room, and the second shows the room with nobody in it. It’s an existentialist witticism, or maybe Freud’s fort-da taken super-literally. Does the room still exist when nobody but God is seeing it? …well, actually, you the viewer take the place of God here in Bishop Berkeley’s familiar solution to the problem of not just “why is there something rather than nothing?” but “how do we know there is still something there if we aren’t perceiving it?” Whole realms of theism versus secular humanism come into play in one modest jump.

It is all such a catalogue of philosophical hilarity, a clearly fictional chronicle of an appealing imaginary cast of characters being bounced through incongruously set-up situations, that it comes as a surprise to learn these are all based upon Stansell’s recollection of real family stories.

The character named Danelle O’Toole isn’t labeled “future bakery employee” in a Catholic-schoolroom scene (a work not in this exhibition) to signify the dead-end first-job prospects of students of Everyschool in smalltown America. (The atmosphere is distinctly un-urban, as even cities tended to be in 1950s children’s books). As we learn from The First Day at Work, Antonucci’s Bakery was a real place, a place where stale bread was gotten rid of by feeding the birds, a place as real as big yellow taxis. Or at least that is how Whitney Stansell, as a child, imagined the scene from the tale told by her mother.

So we have to rethink all these pictures as renderings of what happens to history when it is filtered through would-be true stories, and when the events turned into narrative are processed by the mind of a child for whom the 1950s are very, very far away, a time-before that can only be imagined. There are structures of narrative at work, and the tiresome theories of narratology could come into play if we worked at it for a while.

The strategies of the New Yorker cartoon are still there. Children’s books didn’t number the objects being named, except in terribly serious maps that didn’t try to tell the story at the same time they were giving a key to who and where the people and things and places were.

But now we know that this iconography really is an iconography, in more than one sense of “icon.”

There are layers upon layers of real family history in anyone’s biography, and tales of the attempts of a child to make sense of them can be poignantly amusing. Funny stories frequently contain the remembrance of things past that were, at the time, not fun at all.

There is no such sense of sadness in Stansell’s paintings. The family drama has to be imported, though once known it is hard to get rid of again.

Timothy Tew seems to be drawn to artists whose humor masks difficult subject matter: Consider Jennifer Cawley, whose bunnies and megaphones turn out to recount the challenging history of Northern Ireland.