Several writers have suggested that today’s America is trapped in an “epistemic crisis.” What the writers mean is that America is divided into groups that do not accept one another’s sources of information as communicating anything that could be called knowledge, or even evidence that could lead to coherent knowledge. There are no generally accepted authorities whose investigations cannot be called into question as “completely fake.” The paradoxical result is that completely fake stories can become widely accepted in a matter of hours; made up out of nothing by an online writer, illustrated with miscaptioned photographs stolen from unrelated articles, a fantastic tale will be repeated as truth so often that it becomes the top result in a websearch on the topic.

Of course, this dynamic played out in past eras, only more slowly. Before the invention of photography, woodcuts provided visual confirmation for the bizarre tales that circulated on broadsides, and before that, oral tradition elaborated ever more fantastically on fabricated narratives. Wise souls long ago learned to ask whenever possible for first-person confirmation, or “I’ll believe it when I see it,” which wiser theorists of knowledge almost as long ago corrected to “I’ll see it when I believe it.” What we see is partly determined by what we expect to see. Therein lies a larger issue, quite apart from the specific crises in knowledge today, that deserves the exploration that it has received in the autumn of 2017 in two Atlanta art exhibitions. (Actually, there have been at least two other exhibitions that raise the issue by implication; for my response to one of these, an Agnes Scott College exhibition on artists’ response to climate change, see—as of November 13, 2017—here.)

These two or three independently conceived but intimately related shows should have dominated artworld conversation, but life and larger epistemic crises tend to intervene. As it is, the exhibition that closed on November 8 stirred almost no conversation, and the one closing on December 3 deals with such vast hypotheses that its central thesis remains elusively but enticingly out of focus.

Beth Lilly’s “Knowing and Not Knowing,” a midcareer retrospective curated by Marianne Lambert at Swan Coach House Gallery, incorporated our central theme in its very title. And yet the title yields several different meanings, just as does “Medium” at the Zuckerman Museum of Art. But let the Zuckerman’s tales of mediums and media remain untold for the moment; we have an epistemological journey to make with Beth Lilly and the limits of story, history, and photography.

Lilly tests the limits right up front with The Oracle@WiFi and Every Single One of These Stories Is True, both of which series have been published as books as well as the individual prints from which the photographs on exhibit were extracted. Taken together, the two offer an impressive range of reflections on evidence, imagination, and rules of evaluation.

The Oracle@WiFi came about as an outright fiction about divination, but one enacted in real time. Lilly stated outright that she made no claims to oracle status, but would play the role by taking three photographs in response to a question not yet asked, when the questioner phoned to request a reading. After taking three photographs in quick succession in her immediate surroundings, Lilly would transmit them to the questioner while asking what question they had had in mind. Oracle and querent would then discuss the possible meaning of the photographic outcome. Often the images would bear an uncanny relationship to the details of the question, as when a question about “choice” resulted in three photographs of situations in which choices had to be made among multiple objects or options. Often the images were more ambiguously related to the original question.

The process of interpretation involved extracting meaning from images created without prior knowledge of the situation for which they would be asked to provide data. What is of interest here is less the mind’s ability to project meaning into any unconsciously assembled pattern (for Lilly was not snapping pictures randomly, but rather seeing subtle patterns in the world around her, as any photographer does), but rather, the uncanny parallels between Lilly’s arbitrary pattern and the words in which a large or quite specific topic had been expressed. The correspondences were enough to make any of Lilly’s pronouncements seem prophetic, even as she made no claim to actual knowledge of the future.

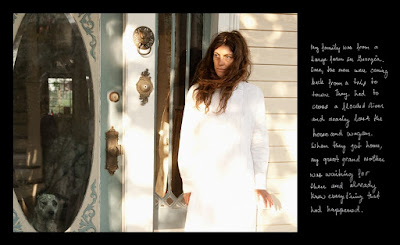

The ambiguity expressed in this postmodernized version of prophecy is reinforced by the staged re-enactments of Every Single One of These Stories Is True. Lilly holds firmly to the veracity of every story told in the handwritten text framed alongside the staged version of the episode, even though—and/or because—all the stories have the air of tall tales. Lilly’s great grandmother knew all the details of a road mishap before the men to whom it happened had arrived home to tell them. A toy red elephant seen in a dream appeared in reality years later, in a bowl where neither Lilly nor her housemate had placed it.

These tales are placed under suspicion only by Lilly’s presumably forthright confession of possibly unreliable memory and outright mental illness in family members. One of Lilly’s aunts believed that any lost item had been stolen by the hippie she was convinced was hiding in her basement.

Lilly herself recalls that her earliest childhood memory involved finding her cousin’s birthday gifts wrapped in black paper. “Later, I asked my Mom why she’d wrapped these in black paper. She said that had never happened. She said it must have been a dream. Maybe, but she has schizophrenia so I’m not sure I can trust her memories.”

This witty double spin on the reliability of memory—each party casting doubt on the accuracy of the other’s recollection—foreshadows the games Lilly will later play with the theme of “knowing and not knowing”—not, be it noted, “knowing or not knowing.” All of us know and do not know at the same time, although what is known and not known shifts according to the situation.

Sometimes this involves simple obliviousness, as in a hilarious set of staged and photocollaged images in which happy families are photographed against a green screen and scenes of impending or already present disaster are inserted behind them, creating a comic tableau of “What, me worry?” as their world collapses without their knowledge. Other obliviousness is captured documentary-style, in photographs of drivers in their cars on the Interstate who are clearly encapsulated in their own private worlds, unaware of the gaze of others.

Lilly titles these latter images with texts from Chinese fortune cookies (e.g., "You are headed in the right direction. Trust your instincts."), linking them to her fascination with our need to define the future, or if possible, to foretell it with certainty.

Lilly also has photographed her own partial view of things seen from the road, or of landscapes at night where what is concealed by darkness creates a sense of uncertainty that translates more often into pleasing mystery rather than threat. Once again, what we see depends on what we believe. A suburban street can seem poetically placid or harmlessly spooky, but the same scene looks considerably different with the prior expectation of lurking intruders or predatory animals.

Lilly also has photographed her own partial view of things seen from the road, or of landscapes at night where what is concealed by darkness creates a sense of uncertainty that translates more often into pleasing mystery rather than threat. Once again, what we see depends on what we believe. A suburban street can seem poetically placid or harmlessly spooky, but the same scene looks considerably different with the prior expectation of lurking intruders or predatory animals.

This sense of shifting perceptions or intrinsically blurry contexts for perfectly clear visual images carries over into “Medium,” the Zuckerman Museum of Art’s approach to our experience of the invisible world and the evidence by which we discern its existence or the aftermath of the ways in which we interact with it. “Invisible” is not always the same as “unheard”; the ambiguities of the auditory are so much a part of this exhibition that its catalogue incorporates a vinyl record alongside a poster documenting the essential facts about the artists and archives that appear in it.

Here it’s best to divide the subject matter into categories in a way that the exhibition itself doesn’t. The fact that the categories will still overlap, or that it will remain uncertain whether one work should be consigned to this category rather than that one, will serve as confirmation of the exhibition’s complex hypothesis about the indefinability of human beings’ transactions with the world of spirits, regardless of whether the spirits are real entities (or evidence interpreted as real entities), traces of past events turned into immaterial memories, or conscious fictions turning immaterial perceptions into material form.

The most documentary portion of the exhibition is, in fact, a collection of fictions intended to deceive, based on the search for hard evidence of spirit encounters in which the investigators for the Society for Psychical Research firmly believed but wished to authenticate. The manifestations of ectoplasm by purported mediums all proved to be hoaxes. Less easily documented phenomena, however, proved to be elusively but persuasively convincing.

This is why later recorded testimony of peculiar encounters and poltergeist phenomena (from the University of West Georgia research program that succeeded J. B. Rhine’s laboratory at Duke University) appears on the LP that serves both as the exhibition catalogue and as an independent piece of sound art, edited/created by Ben Coleman. The paranormal occupies a complex and unstable epistemological space; it skitters off when subjected to laboratory conditions, but manifests anew under circumstances that seem both unpremeditated and genuine. It is frequently difficult to disentangle from imaginative experience.

One of the artworks in “Medium,” by Carrie Mae Weems, responds directly to the nineteenth century’s magic-lantern phantasmagoria or projected images by which ghosts were made to appear, for deception or for pleasurable entertainment. Another work in the show, a complex sound-and-object installation by T. Lang and George Long, evokes the experience of their respective ancestors and the parallel but distinctively different experiences of blacks and whites in the South of yesterday and today, and raises the question of memory and imagination in a more “dematerialized” and/or symbolic form. (Persons wishing more extensive discussions of these artworks can find them in reviews here and here.)

At this point, we may begin to discern the repeated themes of “Medium,” which are those of the dialectic between the deepest parts of historical experience, the role of imagination in mediating between sensory experience and memory, and the insufficiently theorized margins of sensory experience at which we may or may not begin to experience—something else. But what?

A deliciously comic metaphor for all these processes can be found in a historical phenomenon that otherwise seems out of place in the exhibition, the “bone records” of the Cold War era in which music aficionados in the Soviet Union imported contraband styles of Western music by etching the forbidden recordings onto used x-ray sheets in lieu of cutting them onto vinyl blanks. The readily available substitute material thus becomes an inadvertent multilayered metaphor: forbidden knowledge is smuggled past the censor by making use of a material that reveals the depths of the human body, thus permitting the dematerialized experience of music, in which the air around us is altered through the interaction of two objects which in themselves are not music (the record and the record player, the instrument and the body of the performer, the patterned software and the hardware altered by it). The imaginative leap that made the bone records possible and the experience of forbidden knowledge that came from playing them constitutes the contribution of what used to be called “the human spirit” or “the human imagination.”

What happens to that spirit upon bodily death, and whether that spirit co-inhabits the world with other spirits that are not human, is the subject of the history of religions, although that history overlaps significantly with the history of art, thus making “Medium” a feasible exhibition. The show begins in medias res historically, with the rise of spiritualism in the nineteenth century as a way of channeling what had previously been contained within religious strictures dissolved by newfound skepticism. The Society for Psychical Research and its counterparts in Europe arose as efforts to bring a scientific spirit of analysis to the exploration of the margins of the human experience. Today’s firm demarcation between experience restrained by religious dogma and denied by professional skeptics has relegated the paranormal to the realm of popular entertainment, as P. Seth Thompson’s overlap of movie stills from Poltergeist indicates (while giving us a glimpse of how the medium of the movies operates on our inward spirit). In this cultural climate, artists such as Stephanie Dowda are left to create their own visual metaphors with which to cope with the traces left in memory and history in the wake of a mother’s death. Dowda’s photographs of landscapes intersected by overlapping straight lines are curiously reminiscent of the photographs in which the late Gretchen Hupfel made visible the currents of energy carrying the invisible signals of our information media through the atmosphere. We live in a torrent of data of which we are unaware until it finds a channel.

Whether we leave invisibly charged traces on the objects we have used, and whether perceptives can be the channel by which to translate those traces, is explored by Dan R. Talley in his juxtaposition of photographs of ordinary objects with the information that psychics extracted from them at his request. Or rather, they are juxtaposed with the story about extracting that information; as with the nineteenth-century pseudo-mediums whose faked ectoplasm is both ridiculed and transmuted into a different metaphor in Lacey Prpic Hedtke’s contemporary photographs of the female body, we have no way of knowing whether Talley is giving us a total fiction. (Fernando Orellana’s elaborate machines for detecting the presence of ghosts who might be drawn to the object from their past contained in the machine seem far more like a playful put-on with serious head-scratching at the edges; Talley’s dryly analytical account of his concept-laden process feels authentically earnest.)

Any account of any experience, whether backed up by ambiguous physical evidence or not, is potentially fraudulent. (See: “epistemic crisis,” at the beginning of this essay, regarding what happens when this epistemological truth rots the shared sense of trust on which society depends.) Hence it is important that “Medium” includes artwork from two encounters with the spirit world for which we have trustworthy observer data regarding the felt authenticity of the artist’s experience. For the sake of moving towards a phenomenology of the encounter with the invisible world, it seems equally important that they come from opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, and of almost every other conceptual spectrum one cares to create.

J. B. Murray’s “spirit writing,” which he deciphered by reading the revelations through a jar of water drawn from a well on his property, eventually morphed into quasi-figural imagery that he interpreted as illustrating the punishments waiting in Hell for the unrepentant. Illiterate and rural, Murray believed himself “in the hand of the Holy Spirit” (to quote the title of Mary Padgelek’s book about him) after “the sun came down” and the sun plus the rainbow from his garden hose (cf. the 17th century German mystic Jakob Boehme’s “light on the pewter dish”) gave him the power “to see what other folks can’t see.” Although the spirit writings acquired their vivid palette only after artist Andy Nasisse made art materials available to Murray, there is no reason to believe they fail in any degree to reflect the visions of the inner world in which, as Murray put it, “Jesus is stronger than hoodoo.” At the same time, they are deeply creative expressions of Murray’s own spirit (or personal psychology); no other visionary in the rural South produced drawings/writings exactly like Murray’s.

Shana Robbins produces a glitzy response to her own encounters with the spirit world that she has experienced in ayahuasca sessions in actual South American jungles and in self-invented sites for spiritual encounter from Iceland to downtown Atlanta. There is no reason to suppose her creative mythology is any less authentic than J. B. Murray’s. If we have difficulties with any aspects of Robbins’ practice, it is because we have difficulties with the aesthetics of the social milieu from which her practice arises.

Is the practice itself, regardless of the aesthetic terms in which she chooses to cast it, sufficiently efficacious to have penetrated at least the margins of the phenomena, phenomena to which the history of religions gives abundant testimony? How can we do justice to the question of whether or not someone’s practice is efficaciously transformative, rather than dismissing it ipso facto as a simple piece of theatre? Might we be able to assert responsibly that the contours of such practices cannot be adequately mapped by cheap reductionisms? Can we make such an assertion even though we claim (as we must do as moderns) that the phenomena encountered in such practices, phenomena of which most of us have had no direct experience, are given to practitioners through cultural and biological filters—and that these filters make it difficult to discern, whether from the inside or the outside of the practice, whether there is anything authentically “other” occurring?

Can we compose a theory that acknowledges the role of imaginative discourse and composition in the creation of spiritual experience as well as of all forms of art, without reducing the former to a version of the latter? Can we, as Ben Coleman’s catalogue essay/liner notes imply, devise a method of investigation that fully incorporates aesthetic and spiritual experience in a theoretical format that does justice to the full dimensionality of both?

This epistemological issue is what I find most interesting, but it isn’t the only one that curators Justin Rabideau and Teresa Bramlette Reeves have pursued. As I have implied by word choices here and there, we are “haunted” by history, memory, and the gender and ethnic categories into which we are born. There is a reason that the metaphor of ghosts and haunting is used so often to describe personal obsessions and personal and collective trauma, and the show is as interested in that as in the ontological status of disembodied visitors. A catalogue of considerable dimensions could have been compiled that unpacks all of these implications and cross-connections.

However, the vinyl record (with optional digital download of its contents) that constitutes the exhibition catalogue is not that sort of document. It incorporates the show’s auditory aspects (the things that have historically been left out of hard-copy exhibition catalogues, except in those few catalogues containing a supplementary CD or DVD) into a creative anthology of sound art in which documentation blends with experimental compositions. The spectrum of responses that runs between raw experience and refined artworks is thus honored, even as it is obliquely analyzed in the liner notes. The show’s visual aspects are illustrated in the folder of artist statements and biographies accompanying the album. This one-page format allows for the concurrent perusal of the entire range of aesthetic and evidentiary material in this remarkable exhibition, and thus permits the formation of hypotheses along the lines that I have here suggested.

I still would have liked to have a conventional catalogue full of scholarly essays with footnotes and bibliography. But had Reeves and Rabideau gone that route, this present essay would have been impossible. It is far better that they chose not to foreclose our options on a topic on which the options ought to be left as wide open as responsible analysis will permit.

—Jerry Cullum, November 12, 2017